Learning, Legacy, and the New Hope School: Daniel Garber, His Circle, and the Art of Transmission

Learning, Legacy, and the New Hope School

Daniel Garber, His Circle, and the Art of Transmission

Edited by: Christian Answini | Senior Fine Art Specialist

In the early decades of the twentieth century, a remarkable concentration of artistic talent took root along the Delaware River in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Drawn by the region’s distinctive light, rolling terrain, and slower pace of life, painters including Daniel Garber, John Folinsbee, George William Sotter, Walter E. Baum, and William Francis Taylor formed what is now recognized as the New Hope School of Pennsylvania Impressionism. While each artist developed a highly individual voice, they were united by shared values: close observation of nature, disciplined studio practice, and a deep commitment to learning as both process and tradition. Unlike many American Impressionist circles that emphasized individual genius or stylistic rebellion, the New Hope School was defined by continuity. Instruction flowed between formal institutions and informal settings, between academies, studios, and local gathering places. Artists taught, mentored, critiqued, and learned from one another. Paintings produced within this environment often reflect not only aesthetic concerns, but also a broader culture of education and exchange.

_Badura_Frame__5001.jpg)

At the center of this tradition stands Daniel Garber, a pivotal figure whose influence extended far beyond his own canvases. His painting School Days, offered in the upcoming March Fine and Decorative Arts auction, serves as an especially fitting lens through which to examine the educational spirit that shaped the New Hope School and the artists who emerged from it.

Daniel Garber and School Days

Daniel Garber (1880–1958) occupies a singular position within American Impressionism. Trained at the Art Students League and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Garber achieved early acclaim for his luminous landscapes and refined compositional structure. Yet his legacy rests as much on his role as an educator as on his achievements as a painter. Beginning in 1909, Garber taught at the Pennsylvania Academy for more than forty years, shaping generations of artists through an approach that balanced academic rigor with impressionist sensitivity.

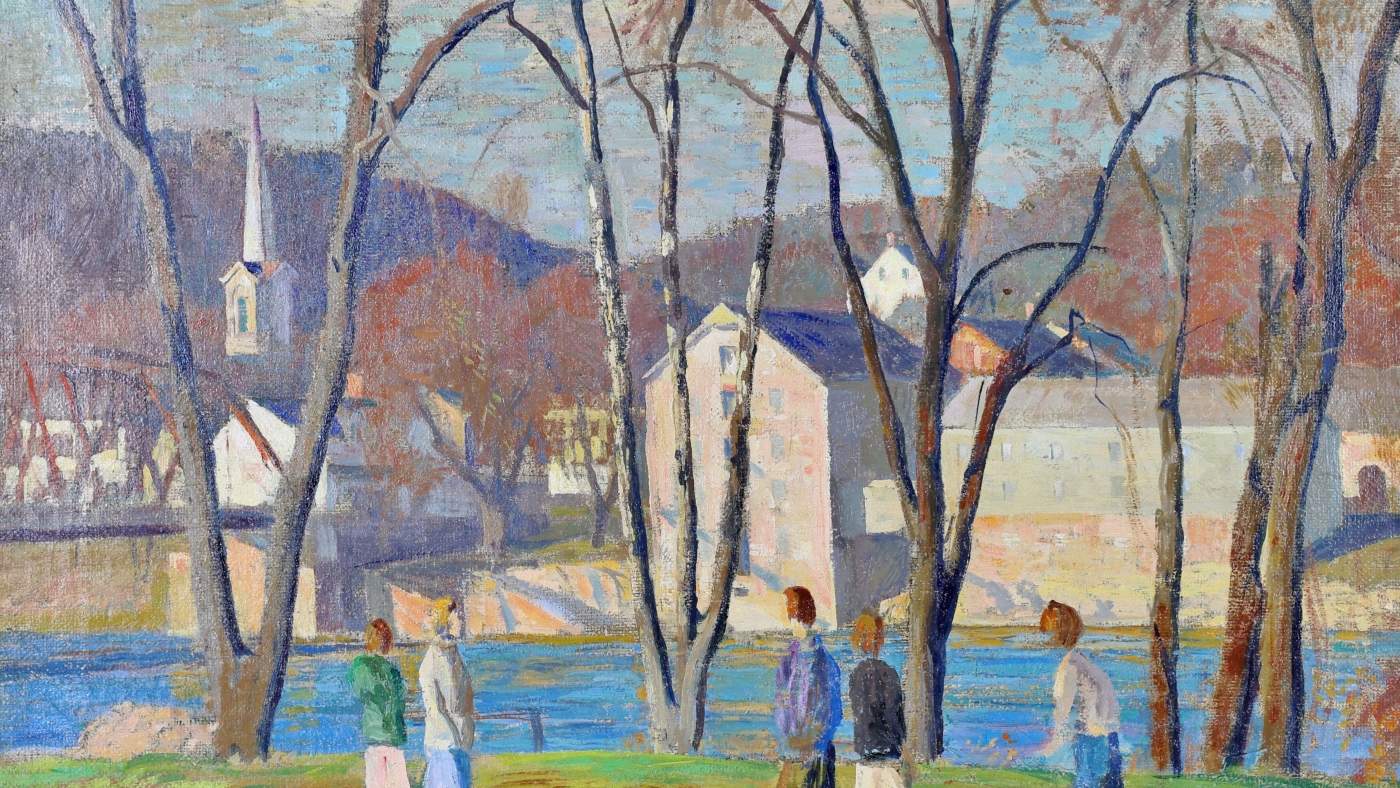

Painted later in his career, School Days reflects a subtle but meaningful shift in Garber’s work. Rather than focusing solely on landscape, the composition incorporates figures within a communal setting. A small group of women and children gathers along the riverbank near a schoolhouse, framed by bare trees and the familiar architecture of the New Hope area. The figures are understated, integrated into the scene rather than emphasized as portraits, yet their presence grounds the painting in daily life and shared routine.

The subject matter operates on multiple levels. On its surface, School Days depicts a quiet moment at the end of the day, rendered with Garber’s characteristic restraint and harmony of color. On a deeper level, the painting reads as a meditation on education itself. The schoolhouse stands as a symbol of instruction and continuity, while the surrounding landscape situates learning within lived experience and place. This alignment mirrors Garber’s philosophy as a teacher, rooted in observation, discipline, and sustained engagement with one’s environment. The painting’s original Bernard Badura frame reinforces this narrative. Badura, a former student of Garber at the Pennsylvania Academy, became the preeminent frame maker for the New Hope School. His hand-carved frames were conceived not as decorative afterthoughts, but as integral components of the artwork, designed to enhance composition and color. The presence of a Badura frame on School Days represents a tangible extension of Garber’s pedagogical reach. Teacher and student are united through both instruction and craftsmanship. In this sense, School Days functions as both artwork and artifact. It embodies Garber’s commitment to teaching, his belief in disciplined practice, and the educational ecosystem that sustained the New Hope School.

Walter E. Baum and the Institutionalization of Art Education

While Garber’s influence was felt most strongly through his long tenure at the Pennsylvania Academy, Walter E. Baum (1884–1956) represents another essential dimension of artistic education within the region. One of the few members of the New Hope School born in Bucks County, Baum devoted much of his career to building institutions that would nurture future generations of artists.

Baum’s landscapes, often vibrant and structurally confident, reflect a painter deeply engaged with both observation and instruction. His role as founder of the Baum School of Art in Allentown underscores his belief that art education should be accessible, rigorous, and rooted in direct engagement with the world. Baum’s work bridges the intimacy of the New Hope circle with a broader regional mission, expanding the reach of Pennsylvania Impressionism beyond Bucks County itself. In the context of this auction, Baum’s painting stands as a reminder that the New Hope School was not a closed enclave. It was a living network of artists who carried its principles into classrooms, schools, and institutions across Pennsylvania.

__2006.jpg)

William Francis Taylor and Learning Through Place

William Francis Taylor (1881–1965) offers another perspective on the transmission of artistic knowledge. A student of William Lathrop, one of the earliest leaders of the New Hope colony, Taylor absorbed the school’s foundational values through mentorship rather than formal academy instruction. His paintings, often depicting winter villages and rural settings, reveal a painter attentive to structure, atmosphere, and seasonal rhythm. Taylor’s work reflects a belief that learning occurs through sustained engagement with place. His scenes are not dramatic or theatrical, but carefully observed and patiently constructed. This approach aligns closely with the educational ethos of the New Hope School, where artists returned again and again to familiar landscapes, deepening their understanding through repetition and study. Taylor also played a vital role in the artistic community itself, co-founding the Phillips’ Mill Art Association, which became a central exhibition and gathering space for New Hope artists. Through this institution, Taylor helped formalize the exchange of ideas that had long defined the colony.

Peer Learning: Folinsbee and Sotter

Not all education within the New Hope School followed a traditional teacher-student model. For artists like John Folinsbee (1892–1972) and George William Sotter (1879–1953), learning occurred largely through peer exchange and shared experience.

Folinsbee, who settled in New Hope in 1916, brought a bold, direct approach to landscape painting. Despite physical challenges following childhood polio, his work demonstrates extraordinary energy and confidence. His paintings of canals, roads, and hillsides reflect a painter fully engaged with his surroundings, learning through relentless observation and practice. Sotter, by contrast, is best known for his nocturnes and winter scenes. His moonlit villages and snow-covered landscapes reveal a painter deeply attuned to mood and atmosphere. Sotter’s background in design and craftsmanship, including work in stained glass, informed his approach to painting and influenced others within the New Hope circle. Together, Folinsbee and Sotter illustrate how education within the New Hope School extended beyond formal instruction. Artists learned from one another through comparison, critique, and shared commitment to seeing clearly.

___5011.jpg)

A Shared Legacy

Taken together, the works by Garber, Baum, Taylor, Folinsbee, and Sotter offered in this March Fine and Decorative Arts auction tell a cohesive story. They are not simply examples of Pennsylvania Impressionism, but evidence of a living educational tradition. Each painting reflects an artist shaped by instruction, mentorship, and community, whether through academy teaching, institutional leadership, apprenticeship, or peer exchange. School Days stands at the heart of this narrative. Its subject, its execution, and its original Badura frame all speak to the values that defined the New Hope School. Learning was not separate from life or landscape. It was embedded within them.

For collectors, these works offer more than aesthetic appeal. They represent a lineage of American art grounded in discipline, observation, and the belief that knowledge, like painting, is passed from hand to hand and generation to generation.

_5003.JPG)